Canada (Attorney General) v Benjamin Moore & Co, 2023 FCA 168, was a much-awaited decision of the Federal Court of Appeal that was supposed to address the long-standing détente between the Canadian patent office and the bulk of the patent prosecution bar regarding the eligibility of computer-implemented inventions. Spoiler alert: it did not.

There is a lot to unpack in this long-standing issue (a subject ripe for a paper). I spoke about it at last year’s University of Toronto Patent Colloquium following the Federal Court’s first instance decision in Benjamin Moore, and it was a topic that seemed to pick up traction among the lawyers and judges in the audience. This will surely be a disappointing judgment for many in the bar who were hoping for some clarity, no matter which side of the fence you sit on.

A Little Bit of History

In brief (omitting for now the juicy details),1Including some very interesting internal training manuals leaked from CIPO apparently telling the examiners expressly that they do not need to follow the case law on claim construction, a fact which seems to have been lost on the Courts. the gist of the long and tortured history of CIPO’s treatment of computer-implemented inventions is as follows. The patent office has been, generally, reluctant to grant software-like patents for the past 15 years or so. The last major case to address the issue was Amazon.com v Canada (Commissioner of Patents), 2011 FCA 328 relating to Amazon’s “one-click” online shopping patent, which is often (wrongly) summarized as “the case that permitted business methods to be patentable”. One commonly cited rationale for granting Amazon’s patent in that case was that the invention manifested in an application to a physical object, thereby overcoming the prohibition against patentability of “mere” abstract theorems. More on this later.

After Amazon.com, CIPO updated its Manual and created Practice Notices (“PNs”) to deal specifically with computer-implemented inventions, using what is now termed the “Problem Solution Approach”. To oversimplify, examiners would try to identify whether there was a “technical solution to a technical problem” (if yes, patentable; if no, not patentable). In practice, though, it did not matter if a claim contained a physical and essential “computer element” (including where the applicant expressly argued essentiality). If the examiner felt that the problem being solved was not a “computer problem” (e.g. making servers more efficient, which would be patentable) or the solution did not truly require a physical computer (e.g. problems that were impossible to solve without a computer were patentable), then the computer was not an essential element, ergo the invention was unpatentable as a mere scientific principle or abstract theorem.

The patent prosecution bar nearly universally agreed that “Problem Solution” was an improper test, since it nowhere in statute (although some argued that it was at least a useful test).

What of Amazon.com? Amazon.com is often (rightly) said to be the leading case on subject-matter eligibility in Canadian patent law. It was a high-profile FCA case entirely devoted to the issue of whether Amazon’s “one-click” patent was an eligible “invention” under the Patent Act. Curiously though, Amazon.com did not do any of the following: it did not create a generally applicable test for subject-matter eligibility, it did not decide generally that “business methods” were patentable, 2Deciding that something is not unpatentable is not the same thing as deciding that it is patentable. nor did it even decide that Amazon’s invention at issue was patentable. In fact, the FCA expressly declined to construe the claims of Amazon’s patent at all – leaving it for the patent office to decide.3Amazon.com (FCA) at paras 70-74; indeed the FCA expressly rejected the lower court’s construction exercise.

In many ways, Amazon.com was an unsatisfactory decision. Although in result, Amazon was granted its patent, this was only because the Commissioner issued the patent following Court-ordered redetermination. However, there were scant reasons accompanying the grant. (The Commissioner is not obligated to provide reasons when it allows a patent, only when it rejects a patent, and even then, the requirements are not high.) In sum, neither the Court nor the Commissioner publicly construed the “computer elements” of Amazon’s patent, so there was no real precedent on how that should be done, other than with the most generic direction that it should be done with expert perspective in view of the correct legal principles.4 Amazon (FCA) at paras 72-74.

The defining characteristic of the Amazon.com decision was that many things were not permitted – don’t rely on catch phrases,5 Amazon (FCA) at para 53 don’t apply the “scientific” or “technological nature” test, 6Amazon (FCA) at para 57 don’t exclude “business methods”,7 Amazon (FCA) at para 61 don’t apply the “practical application” test,8 Amazon (FCA) at para 69 don’t construe the claims without expert perspective,9 Amazon (FCA) at para 72 etc.

This state of affairs persisted for 10 years, and predictably created a vacuum that became filled by the Commissioner’s PNs and individual examiners’ decisions.

Winds of Change in Choueifaty. Then, in Chouiefaty v Canada (Attorney General), 2020 FC 837, the Federal Court finally had occasion to address the “Problem Solution” approach. The details of the case are not all that important save that it was a patent for managing risk in a financial portfolio where a “computer system” was part of the claims. Consistent with its own practice, CIPO construed the problem to be a financial problem – not a computer problem – and found that the computer system elements were not essential, therefore the solution was abstract and unpatentable. In a relatively short decision of 43 paragraphs (only 12 of which contained analysis), Justice Zinn held that CIPO’s “problem solution” approach to claim construction was incorrect at law and inconsistent with the Supreme Court’s construction framework in Free World and Whirlpool.

Unfortunately, Justice Zinn remanded the patentability decision to the Commissioner for redetermination. Like in Amazon.com, the office granted the patent at issue – although this time it issued brief reasons. Those reasons, however, are curious. Despite the fact that the Court quite clearly stated the Commissioner “erred in determining the essential elements of the claimed invention by using the problem-solution approach”,10Choueifaty FC at para 40. the Patent Appeal Board wrote this in its reasons issuing the patent on remand:

[34] Thus, when carrying out any of the claimed inventions of the second proposed claims, the computer operations performed include those designated in the description as the Choueifaty Synthetic Asset Transformation and Back-Transformation, permitting the optimization to be performed with significantly less processing and greater speed than if ratio R were maximized directly. Accordingly, this can be considered an algorithm that improves the functioning of the computer used to run it, such as described in PN2020–04: the computer and the algorithm together form a single actual invention that has physicality and solves a problem related to the manual or productive arts. (Emphasis added)

This was CIPO applying a new “actual invention” approach in response to the courts. It requires little reading between the lines to see the “problem solution” approach in thin disguise. Here, CIPO found that the solution was a technical solution requiring a computer – since the computer was now deemed essential, it suddenly became eligible subject matter.

Indeed, like Amazon.com, once CIPO granted the patent at issue, the patentee had no grounds to complain – after all, it got what it came for. Said another way, the patentee no longer had standing to challenge the decision. Further, since the matter was moot, the Commissioner saw no need to appeal the Court’s decision in Choueifaty despite the Court calling its decision incorrect.

CIPO issued a new Practice Notice in November 2020 titled “Patentable Subject-Matter under the Patent Act“, which on its own terms is intended to take “into account the recent decision [Choueifaty]” and which expressly states that the previous “contribution” test, “technological solution to a technological problem” and “problem and solution approach” to identifying essential elements “should no longer be applied”. This change was hailed at the time by practitioners, at least publicly, as being more permissive. Yet, a close examination of the new PN suggests that CIPO merely moved the “problem solution” analysis from the step of assessing essential elements into the box of subject-matter eligibility, and renamed it to finding the “actual invention”. Examiners are no longer to consider this test during claim construction per se, but instead are to consider it during assessment of patentability. While laudably correct as a matter of form, this seems somewhat like shuffling the deck chairs.

To wit, here is the old PN2013-03 next to the new PN:

Old PN:

MOPOP 16.02 provides that a computer-implemented invention may be claimed as a method (art, process or method of manufacture), machine (generally, a device that relies on a computer for its operation), or product (an article of manufacture). It also notes that certain subject-matter relevant in the computer arts may not be claimed as such, including computer programs [16.08.04], data structures [16.09.02], and computer-generated signals [16.09.05]. The foregoing guidance remains in force.

[…]

Note that where a computer is found to be an essential element of a construed claim, the claimed subject-matter will generally be statutory. A good indicator that a claim is directed to statutory subject-matter is that it provides a technical solution to a technical problem.

Where, on the other hand, it is determined that the essential elements of a construed claim are limited to matter excluded from the definition of invention (as noted above), the claim is not compliant with section 2 of the Patent Act, and consequently, not patentable.[…]

Where it appears that the computer cannot be varied or substituted in a claim without making a difference in the way the invention works or that the computer is required to resolve a practical problem, the computer may be considered an essential element of the claim.

New PN:

An actual invention may consist of either a single element that provides a solution to a problem or of a combination[15] of elements that cooperate together to provide a solution to a problem. Where an actual invention consists of a combination of elements cooperating together, all of the elements of the combination must be considered as a whole when considering whether there is patentable subject-matter and whether the prohibition under subsection 27(8) of the Patent Act is applicable.[16]

The mere fact that a computer is identified to be an essential element of a claimed invention for the purpose of determining the fences of the monopoly under purposive construction does not necessarily mean that the subject-matter defined by the claim is patentable subject-matter and outside of the prohibition under subsection 27(8) of the Patent Act. In such a case, it is necessary to consider whether the computer cooperates together with other elements of the claimed invention and thus is part of a single actual invention and, if so, whether that actual invention has physical existence or manifests a discernible physical effect or change and relates to the manual or productive arts. (Emphasis added)

In addition, the fact that a computer is necessary to put a disembodied idea, scientific principle or abstract theorem into practice does not necessarily mean that there is patentable subject-matter even if the computer cooperates together with other elements of the claimed invention. If a computer is merely used in a well-known manner,Footnote19 the use of the computer will not be sufficient to render the disembodied idea, scientific principle or abstract theorem patentable subject-matter and outside the prohibition under subsection 27(8) of the Patent Act.Footnote20

And despite ostensibly getting rid of the “technological solution to a technological problem” language, the new PN contains this excerpt:

In the case of a claim to a computer programmed to run a mathematical algorithm, if the computer merely processes the algorithm in a well-known manner and the processing of the algorithm on the computer does not solve any problem in the functioning of the computer, the computer and the algorithm do not form part of a single actual invention that solves a problem related to the manual or productive arts. If the algorithm by itself is considered to be the actual invention, the subject-matter defined by the claim is not patentable subject-matter or is prohibited under subsection 27(8) of the Patent Act.

On the other hand, if running the algorithm on the computer improves the functioning of the computer, then the computer and the algorithm would together form a single actual invention that solves a problem related to the manual or productive arts and the subject-matter defined by the claim would be patentable subject-matter and not be prohibited under subsection 27(8) of the Patent Act. (Emphasis added)

If any practitioner has an interpretation of that latter paragraph that would distinguish it from the former “technological solution” test, I would be very interested in hearing it. To my eyes, it seems CIPO took the Court’s guidance in Amazon and Chouiefaty quite literally – it deleted all “catch phrases”, and “tag words” from its tests 11Amazon FCA at para 53 without changing the substance (perhaps now we are to take to calling it the “computer solution to a problem related to the manual or productive arts”, which is a touch clumsier).

Benjamin Moore‘s Applications

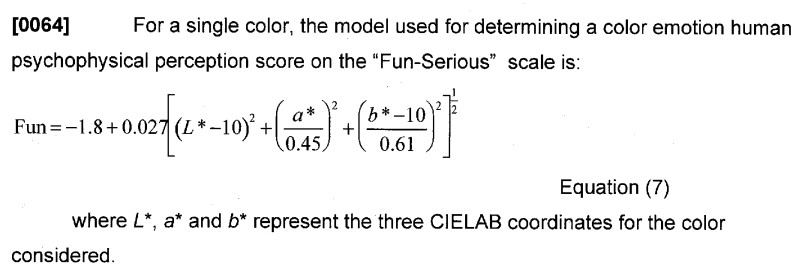

All of this brings us to Benjamin Moore. At issue were two patents that were, in short, about methods of matching paint colours to mood-words. The applicant had, through its own research and consumer surveys, evidently created a form of mathematical relationships between certain words along certain scales and generated numerical associations with those words. For example, in the disclosure of one of the two patent applications at issue:

Evidently, choosing colours is a “serious” matter – but a mathematical equation per se, no matter how serious, is not patentable since it is merely a “scientific principle or abstract theorem”. The claims at issue, however, were “computer implementation” claims, whereby the applicant (their patent agent) had inserted various elements requiring a computer. For example claim 1 of CA 2,695,130 reads “A computer implemented method for selecting colors comprising … associating, in dependence on a mathematical equation that models a human emotional response to color…”. A related application, CA 2,695,148, had more computer-y elements like “storage”, “user input device”, “color display screen”, “visual user interface”, etc.

Patent practitioners will recognize these claims as a result of the common Canadian practice to include as many physical things in a claim as possible in an effort to avoid the “physicality” objection (alive and well after Amazon.com). Indeed, in many cases the claims (and even the disclosure) are drafted specifically to make the physical computer elements essential, under the theory that if the “computer” is a necessary part of the invention, then it cannot be a “mere” abstract theorem but has the required degree of physicality and practical application.

Predictably, in this archetypal case, CIPO refused to grant these applications under the “problem-solution” approach – the applications were not really directed at “computer problems” and did not require a computer to solve. After all, people have been picking paint colours long before computers.

Benjamin Moore appealed CIPO’s decision after 10 years of prosecution, leading to the Federal Court’s decision in Benjamin Moore & Co. v. Canada (Attorney General), 2022 FC 923. In a somewhat unusual procedure, IPIC sought and was granted leave to intervene at first instance. The interests of the parties were of note. Benjamin Moore, the applicant, simply wanted its application to issue and so should have been agnostic to the test per se. IPIC, though, representing the many patent practitioners dissatisfied with the present state of affairs, proposed a specific framework in its intervention brief on how CIPO should address patentable subject matter. Consistent with Choueifaty, the Federal Court found that the “problem solution” approach had problems, but went one step further in adopting IPIC’s proposed framework:

- Purposively construe the claim;

- Ask whether the construed claim as a whole consists of only a mere scientific principle or abstract theorem, or whether it comprises a practical application that employs a scientific principle or abstract theorem; and

- If the construed claim comprises a practical application, assess the construed claim for the remaining patentability criteria: statutory categories and judicial exclusions, as well as novelty, obviousness, and utility.

At least three interesting points arose in Benjamin Moore FC.

First, the IPIC “framework” was no test – it simply sets out the order of operations by which CIPO should determine patentability, ensuring that claims construction should come first. However, nothing in either IPIC’s “framework” or the Federal Court’s reasons addressed what should be eligible subject matter in relation to computers and software. The Court simply held that the “problem solution” approach was incorrect and re-affirmed the state of jurisprudence from Shell and Amazon. In that sense, Benjamin Moore FC did not move the needle much, if at all. The reader was still left with the question of what, precisely, is required to patent a computer-implemented invention?

Second, CIPO had already replaced its practice notice to replace the “problem solution” approach to the “actual invention” approach – but this was done after it rejected BM’s patent. The Federal Court could not directly address the new Practice Notice given that it was not the subject of appeal, but it did not escape the Court’s notice that the old approach was still embedded within the new approach:

[12] Following Choueifaty, CIPO issued an updated Practice Notice entitled

“Patentable Subject-Matter under the Patent Act”. However, this Practice Notice still includes the problem-solution approach, stating on its page 2 of 5 that“An actual invention may consist of either a single element that provides a solution to a problem or of a combination of elements that cooperate together to provide a solution to a problem”.

Third, the Federal Court specifically ordered CIPO to conduct a redetermination with the IPIC framework. A typical order on an appeal or judicial review would read something like “appeal/application allowed, matter to be sent back for redetermination in accordance with these reasons”. Indeed, if the Court’s order read like this, there would have been little to appeal since one can only appeal an order, not its reasons (see below). But the FC, probably wary that CIPO would “interpret” away its judgment on redetermination, specifically put the test in the order itself.

The Procedural Problems of Benjamin Moore FCA

Unsurprisingly Benjamin Moore was appealed by the Commissioner of Patents. The appeal, the FCA noted, was “most unusual for a variety of reasons” [10]. As it turns out, this seemed to become a case where the procedural cart drove the substantive horse. The Commissioner, unusually for an appellant, was in agreement that it erred at law in using the “problem solution” approach and was content with redetermination – it only took issue with the inclusion of the IPIC framework in the order. The respondent Benjamin Moore was also content with the order below but was left in the awkward position of defending the IPIC framework, which was not a test it proposed in the first place. The appeal also attracted the intervention of not just IPIC, but also two insurance industry associations who had an interest in clarifying the test for patentability. IPIC, as an intervenor, was supposed to be neutral to the disposition of the case, but of course it was defending its own test and no matter how it was framed, was surely arguing that the appeal must be dismissed.

The FCA admonished all parties for this unusual posture, observing that it was in effect being asked to provide a binding opinion as a reference on the meaning of “invention” under s. 2 of the Patent Act. Instead, given that nobody was disputing the merits of the decision below per se, the FCA noted it was “premature” and “quite unwise” to “settle issues” that are “yet to be properly considered by any court in Canada” [13].

That was, however, the point. It is quite clear from the procedural history that the entire appeal from the CIPO level all the way up to the FCA was developed as a kind of “test case” precisely to generate a clarifying decision.

Nonetheless, the FCA was not willing to play ball – its opinion, at its shortest, was there was already sufficient guidance in Amazon.com (a now-13-year-old case that is in many respects difficult to understand and apply). The hypothetical issues should be left for an “appropriate case” [81], presumably meaning a case where the applicant and Commissioner actually disagreed and under the new Practice Notice rather than the old one.

I feel compelled to note here that it’s difficult to see what would be a more “appropriate case”. If it were not for CIPO’s amendment of its practice notice between its final rejection and the appeal, this seems like it would have indeed been the appropriate, if not perfect, case. Since it is CIPO’s practice being scrutinized, it is not an issue that comes up in party-party litigation. Amazon.com itself was an appeal from a Commissioner’s decision that is now regarded by the FCA itself as the jurisprudential starting point for patentability of subject matter. It should be noted Amazon.com involved both a 197-paragraph decision by the Commissioner and a detailed analysis by the judge at first instance before it went to the FCA. But, if the FCA was waiting for another decision like this, it could be in for a long hibernation.

A legal realist’s take is that the Court’s rationale can be taken as an instruction manual for administrative bodies (here, CIPO) on how to appeal-proof their decisions. Step 1: delay making a decision. Step 2: issue decisions with minimal reasons at first instance. Step 3: when appealed, but before hearing, change the practice and promise to do better next time. Since the Courts have a habit of remanding the decision instead of substituting its own decision (even in the case of a correctness appeal on a question of law, as here), this seems to be a fairly foolproof method.

This is not entirely tongue-in-cheek. The Benjamin Moore applications were filed in 2008, like the one at issue in Choueifaty. Neither case was appealed until 10-15(!) years until after their filing. Nor could they realistically have been appealed earlier. During prosecution the applicant is generally at the mercy of the examiner. Most of these computer-related inventions were stuck in prosecution for many years while CIPO was sorting out its own practice on how to address them, and the Amazon.com decision in 2010 caused further delay when CIPO revised its own guidance and revisited previously-rejected applications. Further, if an applicant is making bona fide efforts to obtain a patent rather than a test case, it is actually quite difficult to get a “final” rejection from the examiner in order to trigger an appeal deadline under ss. 40-41 of the Patent Act. This does not even mention the internal procedure at the Patent Appeal Board, which is itself backlogged and may take up to 2 years for a decision.

In short, to practitioners, it is unsurprising (but highly disappointing) that a case like this took 15(!) years to get to the FCA – by which point the patentee’s 20-year monopoly, calculated from the filing date, is all but over. What incentive does any individual applicant have to expend the resources for this fight?12I understand that IPIC may have made a variation of this argument above, though, it seems perhaps not strongly enough. The FCA seemed to have very little time for this issue and gave more than a hint of disapproval at the fact that the respondent BM seemed to agree too readily with the intervenor IPIC.

What did the FCA decide?

On the “merits” of the judgment, the FCA rejected the IPIC framework and allowed the appeal. It seems that the primary legal (as opposed to policy) reason given by the FCA was that IPIC’s three-part framework placed s. 2 subject-matter eligibility in step 2, before consideration of other validity issues such as novelty and obviousness in step 3. This seemed relatively uncontroversial but was seized on as incorrect – since, in the FCA’s view, there might be considerations relating to “novelty and ingenuity” in assessing patentability of subject matter under s. 2. The FCA reviewed the case law at length in coming to this conclusion, finding that the word “invention” in s. 2 itself implied “ingenuity”, so that it cannot be divorced from eligibility.

That, too, seems an uncontroversial position, but I must admit after reading the decision several times, it is not clear to me what role “ingenuity” is supposed to play in the analysis as distinct from “obviousness”.13 The FCA at [71] quotes Justice Binnie’s “hard coinage” passage for “new, ingenious, useful and unobvious disclosures”. Now, that is a fine statement such as it is, but the FCA expressly holds “ingenious” different than “unobvious” – hereby opening up a new door for litigants. It should be mentioned that when Justice Binnie was making this judgement the world “obvious” did not even appear in the Patent Act and it could be suggested that Binnie was simply reciting the obviousness requirement. The FCA does not seem to recognize the irony that, in [74], in reviewing the Australian High Court judgment, the FCA conflates the word “ingenuity” with “non-obviousness”. It is one thing to say these concepts are related (they are), but it is quite another thing to say that they can’t be decided separately. After all, in practice, something has to come first. Whether that is a matter of form or a matter of law may be up for debate, but surely the Court cannot be suggesting that it is an error to conduct validity analyses in sequential order – indeed, the courts do this routinely when it decides validity on one ground and declines to determine validity on another ground.

More importantly, perhaps, is that the FCA seemed to seize on the order of operations in IPIC’s steps 2-3 without addressing the core issue at all – what role should claims construction, and particularly, the construction of essential elements, play in determining subject-matter eligibility? The entire thrust of the IPIC framework is that the eligibility of subject matter should be assessed based on the essential claim elements as purposively construed – implicitly meaning if the physical computer elements are found essential then at least it might overcome a physicality objection. It seems entirely beside the point whether subject-matter eligibility came before novelty/obviousness and other grounds of validity.

The FCA’s analysis glossed over this problem. It seems that a simpler solution rather than rejecting the framework entirely would have been to collapse the test into two steps – first construe the claims and their essential elements, then determine validity based on those elements. Perhaps that was too trite for the Court. Yet by rejecting the test it has once again given permission to CIPO to revert to its practice of assessing subject matter based on the problem or invention including ascertained from the disclosure.

Indeed, the FCA came very close to explicitly endorsing the “problem solution” approach. It certainly did so implicitly at paragraphs [41]-[42], when it stated that “there is nothing ground breaking” about understanding the problem and the solution and that it is “trite law” that he purpose and mischief intended to be addressed by the “legislator” (implying the patentee is a legislator) is a “relevant consideration”.

The Court even makes a perplexing comment at [42] when it suggests that the identity of the patentee company (who is not the inventor) is a relevant consideration. To my eyes this seems to be quite superficial – the FCA’s position seems to be that BM is just a paint company trying to monopolize selection of colours “when used by artists, garden designers, furniture companies, or for organizing one’s wardrobe” that happens to use a computer. This extends “problem solution” beyond even the disclosure, by reference to some external evidence about the applicant’s business. Put another way, why can’t a paint company be trying to address a technical problem of generating precise colour pairs based on particular input values, the solution of which requires a computer?14(Here we can also observe why framing of the “problem” and “solution” will often dictate the result – if one adds technical context to the problem, one can almost certainly find a technical solution to match that context.) Indeed, Amazon was just a “book company” once upon a time, before it realized it could sell its web services and logistics network to third parties.

The FCA’s motivation, perhaps, can be found later in its decision – though it is not articulated as such. The Court suggests that, regardless of whether a physical computer element is essential in the claims, simply doing something that was done before, but on a computer, is not patentable. What it probably really means to say is that doing so is obvious, or “not ingenious”. And there is much merit in that position – surely, doing a thing that was done before but now in an automated fashion using a computer does not make it per se inventive. Unfortunately, this is not what the Court actually said in rejecting the IPIC framework.

The decision dances curiously around the issue that the FCA implicitly or inadvertently acknowledges at [50]: computer-implemented inventions are, of course, not a distinct category under section 2 of the Act. The issue, however, is that the Commissioner (not BM, not IPIC, and not the FC) treats computer-implemented inventions differently – they do so explicitly in its own Practice Notice on Computer-Implemented Inventions and in its own section of MOPOP, something not done for any other field.

Further, in [86]-[87], in its concluding remarks on how to consider “contribution” to the field in the analysis, the Court dances around the point again. In the Schlumberger case cited, there was a contribution to human knowledge – the mathematical formula – but it was decided that because the incremental knowledge (the formula) was not patentable as it was “merely” an abstract theorem, the whole claim was impermissible. This is probably the question that the Court ought to be looking at revisiting – if you have one element (a mathematical formula) that is abstract but the remaining elements are physical, does the whole invention (a widget that applies the formula) benefit from patent protection?

This fundamental tension is why parties are unsatisfied with the current state of the law. The point of distinction drawn at [88] between Mobil Oil and Schlumberger, by the Court’s own terms, is that the output of the method was a “new enhanced seismogram” (a physical or tangible thing). Assuming this is the correct test, then Schlumberger should have been patentable if they simply added the element of “outputting the results to a char on a physical screen”. Indeed, this is what patent agents and their clients try to do under present practice – yet CIPO plainly does not accept this distinction, with good policy justification perhaps but unsound legal justification.

Even more flummoxing, after spending the bulk of the decision criticizing the court below and the litigants for arguing a hypothetical and deferring the proper test to another day, the FCA at [90]-[94] creates an analogy which ends curiously like a test. Particularly, the FCA stated, after comparing a hypothetical choose-your-own-recommendation book to a computer algorithm doing the same thing:

[94] In other words, if the only new knowledge lies in the method itself, it is the method that must be patentable subject matter. If, however, the new knowledge is simply the use of a well-known instrument (a book or a computer) to implement this method, then it will likely not fall under the definition found at section 2 without something more to meet the requirement described at paragraph 66 of Amazon.

If this is meant to resolve the tension between Shell Oil and Schlumberger, the Court probably should have said so. As it stands, this comment appears in an expressly obiter section of the judgment titled “Additional comments” and was not applied to the case at bar, except in the rather contrived hypothetical offered by the Court.

Benjamin Moore left more questions than answers

It’s hard to find a clean takeaway from this case. The Court not only declined to answer the question posed to it; it created more questions than answers:

- Do “essential elements” of a claim play any role in subject matter eligibility? Left unanswered.

- If all validity grounds are equal, how does “ingenuity” relate to subject matter? New question for another day.

- What, even, does “ingenuity” mean apart from non-obviousness? New question for another day.

- What is the appropriate test for subject matter eligibility? Maybe answered in obiter at [94].

- If CIPO’s “Problem Solution” approach is incorrect, what about its “Actual Invention” approach? Left for an “appropriate” case to decide, hopefully in less than 15 years.

Yet, maybe not all hope is lost. the framework at issue in Benjamin Moore was not really a test at all. It wouldn’t have resolved the central questions plaguing eligibility of computer-implemented inventions anyway. Had that been the FCA’s last word for another decade, it could have been equally disappointing in what it did not say (e.g. the relevant factors for eligibility). Given the FCA expressly left the question open, perhaps on a better record, more refined arguments, and another willing participant, an even better test might arise.

- 1Including some very interesting internal training manuals leaked from CIPO apparently telling the examiners expressly that they do not need to follow the case law on claim construction, a fact which seems to have been lost on the Courts.

- 2Deciding that something is not unpatentable is not the same thing as deciding that it is patentable.

- 3Amazon.com (FCA) at paras 70-74; indeed the FCA expressly rejected the lower court’s construction exercise.

- 4Amazon (FCA) at paras 72-74.

- 5Amazon (FCA) at para 53

- 6Amazon (FCA) at para 57

- 7Amazon (FCA) at para 61

- 8Amazon (FCA) at para 69

- 9Amazon (FCA) at para 72

- 10Choueifaty FC at para 40.

- 11Amazon FCA at para 53

- 12I understand that IPIC may have made a variation of this argument above, though, it seems perhaps not strongly enough. The FCA seemed to have very little time for this issue and gave more than a hint of disapproval at the fact that the respondent BM seemed to agree too readily with the intervenor IPIC.

- 13The FCA at [71] quotes Justice Binnie’s “hard coinage” passage for “new, ingenious, useful and unobvious disclosures”. Now, that is a fine statement such as it is, but the FCA expressly holds “ingenious” different than “unobvious” – hereby opening up a new door for litigants. It should be mentioned that when Justice Binnie was making this judgement the world “obvious” did not even appear in the Patent Act and it could be suggested that Binnie was simply reciting the obviousness requirement. The FCA does not seem to recognize the irony that, in [74], in reviewing the Australian High Court judgment, the FCA conflates the word “ingenuity” with “non-obviousness”.

- 14(Here we can also observe why framing of the “problem” and “solution” will often dictate the result – if one adds technical context to the problem, one can almost certainly find a technical solution to match that context.)

Leave a Reply